The Adcock Range System

By Captain Dick Miller

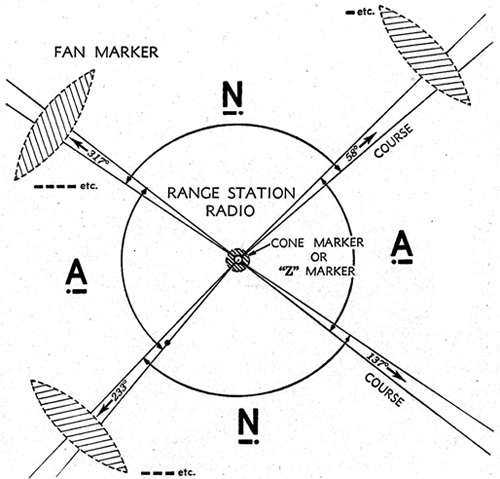

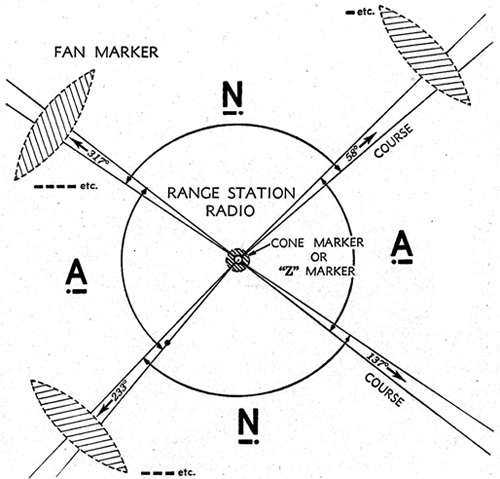

This primary navigation system was comprised of sparsely located Adcock low-frequency range transmitters. Each facility consisted of four legs which could be used as "beams" for navigating either to or from a station on the airways or for shooting low approaches for landing. Each range station emitted audio signals comprised of four quadrants. Two quadrants provided a Morse Code signal of "N" (dash-dot) while the opposing quadrant emitted an "A" signal (dot-dash). Each quadrant overlapped precisely to provide a three-degree leg or beam by meshing the two audio signals to provide a continuous dash or "on course" monotone signal.

Obviously the range stations needed to be located near major airports to provide the approach facility. The four legs of each station could be beamed in a direction to connect with other stations to form a system of "colored" airways. Amber Seven, for example, ran from Miami to Newark. A few fan and marker beacons had been installed at various locations in order to identify a specific point.

Quite often the quadrants were not configured in equal sizes and were descriptively referred to as "crow foot" ranges. Since the beam fanned out three degrees from the station, and was three miles wide at 60 miles out, it was considered standard procedure to fly the right edge of the beam for precise navigation. Also, if you happened to pass another aircraft flying blind at the same altitude in the opposite direction, it was considered enough separation to prevent a mid air collision. For navigation purposes, the only way to confirm whether you were flying toward or away from the station was the use of the volume control. Each pilot developed his own individual volume level in determining a build or fade in signal strength to determine if he was flying to or from the station. There were several elaborate orientation procedures developed for use with the four-course low-frequency range should a pilot become lost. All that technology worked fine in good weather, but storms and static could make it almost useless.

Another characteristic of the low-frequency range was the Cone of Silence immediately above the station, which would denote position. A typical approach involved crossing over the station initially to establish position, flying outbound several minutes on the approach leg, executing a procedure turn and precisely bracket the right edge of the beam while descending to an initial approach altitude. As an aircraft approached the station, the three-degree beam was extremely narrow and practically rocking the wings would transverse the beam into signals of the opposite quadrant. The key was to complete the bracketing maneuvers far enough out to tie down a heading that would only require minor changes near the station.

When the Cone of Silence was passed, a time reference was made for minutes or seconds to go and descent completed to minimum altitude. After visual contact was established with the airport, quite often a circling approach was required to complete the landing. The low-frequency range approach was a very impressive procedure and proof of pilot instrument proficiency. Senior pilots proficient with the procedure often stated, "It separates the men from the boys."

— Excerpt from Dick Miller bio, Wings of Man, by Jack King.

|